Granville number

Contents |

In mathematics, specifically number theory, Granville numbers are an extension of the perfect numbers.

The Granville set

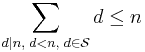

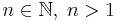

In 1996, Andrew Granville proposed the following construction of the set  :[1]

:[1]

- Let

and for all

and for all  let

let  if:

if:

A Granville number is an element of  for which strict equality holds i.e. it is equal to the sum of its proper divisors that are also in

for which strict equality holds i.e. it is equal to the sum of its proper divisors that are also in  . Granville numbers are also called

. Granville numbers are also called  -perfect numbers.[2]

-perfect numbers.[2]

General properties

The elements of  can be k-deficient, k-perfect, or k-abundant. In particular, 2-perfect numbers are a proper subset of

can be k-deficient, k-perfect, or k-abundant. In particular, 2-perfect numbers are a proper subset of  .[1]

.[1]

S-deficient numbers

Numbers that fulfill the strict form of the inequality in the above definition are known as  -deficient numbers. That is, the

-deficient numbers. That is, the  -deficient numbers are the natural numbers that are strictly less than the sum of their divisors in

-deficient numbers are the natural numbers that are strictly less than the sum of their divisors in  .

.

S-perfect numbers

Numbers that fulfill equality in the above definition are known as  -perfect numbers.[1] That is, the

-perfect numbers.[1] That is, the  -perfect numbers are the natural numbers that are equal the sum of their divisors in

-perfect numbers are the natural numbers that are equal the sum of their divisors in  . The first few

. The first few  -perfect numbers are:

-perfect numbers are:

- 6, 24, 28, 96, 126, 224, 384, 496, 1536, 1792, 6144, 8128, 14336, ... (sequence A118372 in OEIS)

Every perfect number is also  -perfect.[1] However, there are numbers such as 24 which are

-perfect.[1] However, there are numbers such as 24 which are  -perfect but not perfect. The only known

-perfect but not perfect. The only known  -perfect number with three distinct prime factors is 126 = 2 · 3² · 7 .[2]

-perfect number with three distinct prime factors is 126 = 2 · 3² · 7 .[2]

S-abundant numbers

Numbers that violate the inequality in the above definition are known as  -abundant numbers. That is, the

-abundant numbers. That is, the  -abundant numbers are the natural numbers that are strictly greater than the sum of their divisors in

-abundant numbers are the natural numbers that are strictly greater than the sum of their divisors in  ; they belong to the complement of

; they belong to the complement of  . The first few

. The first few  -abundant numbers are:

-abundant numbers are:

- 12, 18, 20, 30, 42, 48, 56, 66, 70, 72, 78, 80, 84, 88, 90, 102, 104, ... (sequence A181487 in OEIS)

Examples

Every deficient number and every perfect number is in  because the restriction of the divisors sum to members of

because the restriction of the divisors sum to members of  either decreases the divisors sum or leaves it unchanged. The first natural number that is not in

either decreases the divisors sum or leaves it unchanged. The first natural number that is not in  is the smallest abundant number, which is 12. The next two abundant numbers, 18 and 20, are also not in

is the smallest abundant number, which is 12. The next two abundant numbers, 18 and 20, are also not in  . However, the fourth abundant number, 24, is in

. However, the fourth abundant number, 24, is in  because the sum of its proper divisors in

because the sum of its proper divisors in  is:

is:

- 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 6 + 8 = 24

In other words, 24 is abundant but not  -abundant because 12 is not in

-abundant because 12 is not in  . In fact, 24 is

. In fact, 24 is  -perfect - it is the smallest number that is

-perfect - it is the smallest number that is  -perfect but not perfect.

-perfect but not perfect.

The smallest odd abundant number that is in  is 2835, and the smallest pair of consecutive numbers that are not in

is 2835, and the smallest pair of consecutive numbers that are not in  are 5984 and 5985.[1]

are 5984 and 5985.[1]

References

- ^ a b c d e "On a Sum of Divisors Problem". Publications de l'Institut mathématique 64 (78): 9–20. 1996. http://www.emis.de/journals/PIMB/078/n078p009.pdf. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ^ a b de Koninck, J.M. (2009). Those fascinating numbers. AMS Bookstore. p. 40. ISBN 0-8218-4807-0.